Baby Boy Weight Chart in Kg 1 Year and 7 Month Old

| Torso mass alphabetize (BMI) | |

|---|---|

Nautical chart showing body mass index (BMI) for a range of heights and weights in both metric and imperial. Colours indicate BMI categories defined by the World Health System; underweight, normal weight, overweight, moderately obese, severely obese and very severely obese. | |

| Synonyms | Quetelet index |

| MeSH | D015992 |

| MedlinePlus | 007196 |

| LOINC | 39156-5 |

Body mass index (BMI) is a value derived from the mass (weight) and height of a person. The BMI is defined as the body mass divided by the square of the trunk summit, and is expressed in units of kg/m2, resulting from mass in kilograms and meridian in metres.

The BMI may be adamant using a table[a] or chart which displays BMI equally a function of mass and summit using contour lines or colours for different BMI categories, and which may use other units of measurement (converted to metric units for the calculation).[b]

The BMI is a convenient rule of thumb used to broadly categorize a person as underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese based on tissue mass (muscle, fatty, and os) and pinnacle. Major adult BMI classifications are underweight (under eighteen.5 kg/chiliadtwo), normal weight (18.5 to 24.9), overweight (25 to 29.ix), and obese (30 or more).[1] When used to predict an individual'southward health, rather than as a statistical measurement for groups, the BMI has limitations that can make it less useful than some of the alternatives, especially when applied to individuals with intestinal obesity, short stature, or unusually high muscle mass.

BMIs under xx and over 25 have been associated with higher all-causes bloodshed, with the risk increasing with distance from the twenty–25 range.[2]

History [edit]

Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian astronomer, mathematician, statistician, and sociologist, devised the basis of the BMI between 1830 and 1850 as he adult what he chosen "social physics".[iii] The modern term "body mass alphabetize" (BMI) for the ratio of homo body weight to squared height was coined in a paper published in the July 1972 edition of the Journal of Chronic Diseases by Ancel Keys and others. In this paper, Keys argued that what he termed the BMI was "if not fully satisfactory, at to the lowest degree equally expert as whatsoever other relative weight index equally an indicator of relative obesity".[4] [five] [vi]

The interest in an index that measures trunk fatty came with observed increasing obesity in prosperous Western societies. Keys explicitly judged BMI as appropriate for population studies and inappropriate for individual evaluation. Nevertheless, due to its simplicity, it has come to be widely used for preliminary diagnoses.[7] Additional metrics, such equally waist circumference, can be more useful.[viii]

The BMI is expressed in kg/yard2, resulting from mass in kilograms and peak in metres. If pounds and inches are used, a conversion factor of 703 (kg/m2)/(lb/inii) is applied. When the term BMI is used informally, the units are usually omitted.

BMI provides a uncomplicated numeric measure of a person's thickness or thinness, allowing health professionals to discuss weight issues more objectively with their patients. BMI was designed to be used as a unproblematic means of classifying average sedentary (physically inactive) populations, with an average body limerick.[9] For such individuals, the BMI value recommendations as of 2014[update] are as follows: 18.5 to 24.nine kg/m2 may indicate optimal weight, lower than 18.5 may indicate underweight, 25 to 29.9 may indicate overweight, and 30 or more may indicate obese.[7] [8] Lean male athletes often accept a loftier muscle-to-fat ratio and therefore a BMI that is misleadingly high relative to their body-fat percentage.[viii]

Categories [edit]

A common utilize of the BMI is to assess how far an individual'southward body weight departs from what is normal for a person's height. The weight excess or deficiency may, in function, exist accounted for past body fat (adipose tissue) although other factors such as muscularity as well impact BMI significantly (come across word beneath and overweight).[10]

The WHO regards an adult BMI of less than 18.5 every bit underweight and may signal malnutrition, an eating disorder, or other health problems, while a BMI equal to or greater than 25 is considered overweight and 30 or more is considered obese.[1] In add-on to the principle, international WHO BMI cut-off points (16, 17, 18.5, 25, 30, 35 and xl), four additional cut-off points for at-risk Asians were identified (23, 27.5, 32.5 and 37.5).[xi] These ranges of BMI values are valid but as statistical categories.

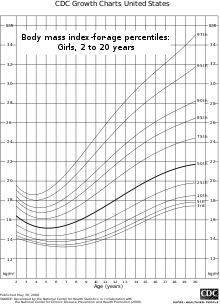

Children (anile 2 to 20) [edit]

BMI for age percentiles for boys 2 to 20 years of age

BMI for age percentiles for girls 2 to twenty years of age

BMI is used differently for children. Information technology is calculated in the aforementioned fashion equally for adults merely then compared to typical values for other children of the aforementioned historic period. Instead of comparing against fixed thresholds for underweight and overweight, the BMI is compared against the percentiles for children of the same sex and age.[12]

A BMI that is less than the fifth percentile is considered underweight and in a higher place the 95th percentile is considered obese. Children with a BMI between the 85th and 95th percentile are considered to be overweight.[xiii]

Studies in Great britain from 2013 have indicated that females between the ages 12 and 16 had a higher BMI than males of the aforementioned historic period by 1.0 kg/mtwo on average.[xiv]

International variations [edit]

These recommended distinctions along the linear scale may vary from time to fourth dimension and country to country, making global, longitudinal surveys problematic. People from dissimilar populations and descent have dissimilar associations between BMI, percentage of body fatty, and wellness risks, with a higher risk of type two diabetes mellitus and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease at BMIs lower than the WHO cut-off point for overweight, 25 kg/gtwo, although the cut-off for observed risk varies among different populations. The cut-off for observed risk varies based on populations and subpopulations in Europe, Asia and Africa.[15] [16]

Hong Kong [edit]

The Hospital Authority of Hong Kong recommends the use of the following BMI ranges:[17]

Japan [edit]

A 2000 study from the Nihon Society for the Study of Obesity (JASSO) presents the following table of BMI categories:[18] [nineteen] [20]

Singapore [edit]

In Singapore, the BMI cut-off figures were revised in 2005 past the Health Promotion Board (HPB), motivated by studies showing that many Asian populations, including Singaporeans, have a higher proportion of torso fat and increased risk for cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus, compared with general BMI recommendations in other countries. The BMI cutting-offs are presented with an emphasis on health risk rather than weight.[21]

United States [edit]

In 1998, the U.Southward. National Institutes of Wellness and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention brought U.S. definitions in line with World Health Organization guidelines, lowering the normal/overweight cut-off from BMI 27.8 to BMI 25. This had the result of redefining approximately 29 million Americans, previously salubrious, to overweight.[22]

This can partially explicate the increase in the overweight diagnosis in the by xx years, and the increment in sales of weight loss products during the aforementioned time. WHO as well recommends lowering the normal/overweight threshold for southeast Asian body types to around BMI 23, and expects further revisions to emerge from clinical studies of different body types.[23]

A survey in 2007 showed 63% of Americans were then overweight or obese, with 26% in the obese category (a BMI of 30 or more than). Past 2014, 37.7% of adults in the United States were obese, 35.0% of men and twoscore.4% of women; class 3 obesity (BMI over 40) values were 7.7% for men and 9.9% for women.[24] The U.South. National Wellness and Nutrition Exam Survey of 2015-2016 showed that 71.vi% of American men and women had BMIs over 25.[25] Obesity—a BMI of xxx or more—was institute in 39.eight% of the U.s. adults.

Consequences of elevated level in adults [edit]

The BMI ranges are based on the relationship between body weight and disease and death.[27] Overweight and obese individuals are at an increased adventure for the following diseases:[28]

- Coronary artery illness

- Dyslipidemia

- Blazon 2 diabetes

- Gallbladder disease

- Hypertension

- Osteoarthritis

- Sleep apnea

- Stroke

- Infertility

- At least 10 cancers, including endometrial, chest, and colon cancer[29]

- Epidural lipomatosis[30]

Among people who have never smoked, overweight/obesity is associated with 51% increase in mortality compared with people who accept always been a normal weight.[31]

Applications [edit]

Public wellness [edit]

The BMI is more often than not used as a ways of correlation between groups related by general mass and can serve equally a vague means of estimating adiposity. The duality of the BMI is that, while it is piece of cake to use as a general calculation, it is limited as to how authentic and pertinent the information obtained from it can be. Generally, the index is suitable for recognizing trends within sedentary or overweight individuals because in that location is a smaller margin of mistake.[32] The BMI has been used by the WHO as the standard for recording obesity statistics since the early 1980s.

This full general correlation is particularly useful for consensus data regarding obesity or various other conditions considering it can be used to build a semi-authentic representation from which a solution tin exist stipulated, or the RDA for a group can be calculated. Similarly, this is becoming more and more pertinent to the growth of children, since the majority of children are sedentary.[33] Cross-exclusive studies indicated that sedentary people can subtract BMI by becoming more physically active. Smaller effects are seen in prospective cohort studies which lend to support active mobility as a means to preclude a further increment in BMI.[34]

Clinical practice [edit]

BMI categories are mostly regarded as a satisfactory tool for measuring whether sedentary individuals are underweight, overweight, or obese with various exceptions, such as athletes, children, the elderly, and the infirm.[ medical citation needed ] Besides, the growth of a child is documented confronting a BMI-measured growth chart. Obesity trends can and then be calculated from the difference between the kid's BMI and the BMI on the chart.[ medical citation needed ] In the United States, BMI is also used as a measure of underweight, owing to advocacy on behalf of those with eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.[ medical citation needed ]

Legislation [edit]

In France, Italy, and Spain, legislation has been introduced banning the usage of fashion evidence models having a BMI below 18.[35] In Israel, a BMI below 18.5 is banned.[36] This is done to fight anorexia among models and people interested in way.

Relationship to health [edit]

A study published by Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in 2005 showed that overweight people had a death rate similar to normal weight people as defined past BMI, while underweight and obese people had a higher decease rate.[37]

A study published by The Lancet in 2009 involving 900,000 adults showed that overweight and underweight people both had a bloodshed charge per unit college than normal weight people every bit defined by BMI. The optimal BMI was found to exist in the range of 22.5–25.[38] The boilerplate BMI of athletes is 22.4 for women and 23.vi for men.[39]

High BMI is associated with type two diabetes only in persons with high serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase.[xl]

In an analysis of 40 studies involving 250,000 people, patients with coronary avenue disease with normal BMIs were at higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease than people whose BMIs put them in the overweight range (BMI 25–29.9).[41]

One study found that BMI had a good general correlation with body fat percentage, and noted that obesity has overtaken smoking as the earth'due south number one cause of death. Just it too notes that in the written report 50% of men and 62% of women were obese according to body fatty defined obesity, while just 21% of men and 31% of women were obese according to BMI, meaning that BMI was found to underestimate the number of obese subjects.[42]

A 2010 written report that followed eleven,000 subjects for upwardly to 8 years ended that BMI is non a expert measure out for the adventure of heart set on, stroke or death. A better measure was found to be the waist-to-height ratio.[43] A 2011 study that followed 60,000 participants for up to 13 years found that waist–hip ratio was a meliorate predictor of ischaemic centre illness bloodshed.[44]

Limitations [edit]

This graph shows the correlation between trunk mass index (BMI) and body fat percentage (BFP) for 8550 men in NCHS' NHANES 1994 data. Data in the upper left and lower right quadrants suggest the limitations of BMI.[42]

The medical institution[45] and statistical customs[46] accept both highlighted the limitations of BMI.

Scaling [edit]

The exponent in the denominator of the formula for BMI is arbitrary. The BMI depends upon weight and the foursquare of acme. Since mass increases to the tertiary power of linear dimensions, taller individuals with exactly the same body shape and relative composition accept a larger BMI.[47] BMI is proportional to the mass and inversely proportional to the square of the superlative. And then, if all body dimensions double, and mass scales naturally with the cube of the height, then BMI doubles instead of remaining the same. This results in taller people having a reported BMI that is uncharacteristically high, compared to their bodily body fat levels. In comparison, the Ponderal alphabetize is based on the natural scaling of mass with the tertiary power of the height.[48]

However, many taller people are non just "scaled upwards" short people but tend to take narrower frames in proportion to their height.[49] Carl Lavie has written that "The B.M.I. tables are fantabulous for identifying obesity and body fat in large populations, but they are far less reliable for determining fatness in individuals."[l]

According to mathematician Nick Trefethen, "BMI divides the weight by as well large a number for short people and too minor a number for tall people. And then short people are misled into thinking that they are thinner than they are, and alpine people are misled into thinking they are fatter."[51]

For U.s. adults, exponent estimates range from i.92 to one.96 for males and from ane.45 to i.95 for females.[52] [53]

Physical characteristics [edit]

The BMI overestimates roughly 10% for a large (or tall) frame and underestimates roughly 10% for a smaller frame (brusque stature). In other words, persons with pocket-sized frames would exist carrying more fatty than optimal, but their BMI indicates that they are normal. Conversely, big framed (or tall) individuals may be quite healthy, with a adequately low body fat percentage, but be classified as overweight by BMI.[54]

For instance, a height/weight nautical chart may say the ideal weight (BMI 21.five) for a i.78-metre-tall (5 ft ten in) human being is 68 kilograms (150 lb). But if that human has a slender build (small frame), he may be overweight at 68 kg or 150 lb and should reduce by 10% to roughly 61 kg or 135 lb (BMI nineteen.iv). In the reverse, the man with a larger frame and more solid build should increment by x%, to roughly 75 kg or 165 lb (BMI 23.7). If ane teeters on the edge of pocket-size/medium or medium/large, common sense should be used in computing i's ideal weight. Even so, falling into 1'southward ideal weight range for height and build is still non every bit accurate in determining health risk factors every bit waist-to-height ratio and actual body fat percentage.[55]

Accurate frame size calculators use several measurements (wrist circumference, elbow width, cervix circumference, and others) to determine what category an individual falls into for a given pinnacle.[56] The BMI also fails to take into business relationship loss of height through ageing. In this situation, BMI volition increase without any corresponding increase in weight.

Proposed new BMI [edit]

A new formula for calculating Body Mass Index that accounts for the distortions of the traditional BMI formula for shorter and taller individuals has been proposed by Nick Trefethen, Professor of numerical analysis at the University of Oxford:[57]

The scaling factor of 1.iii was determined to make the proposed new BMI formula marshal with the traditional BMI formula for adults of boilerplate height, while the exponent of 2.5 is a compromise between the exponent of two in the traditional formula for BMI and the exponent of 3 that would be expected for the scaling of weight (which at constant density would theoretically scale with volume, i.eastward., as the cube of the pinnacle) with height; however, in Trefethen's analysis, an exponent of 2.v was found to fit empirical data more closely with less distortion than either an exponent of 2 or 3.

Muscle versus fatty [edit]

Assumptions nigh the distribution between muscle mass and fat mass are inexact. BMI generally overestimates adiposity on those with more lean body mass (e.chiliad., athletes) and underestimates excess adiposity on those with less lean body mass.

A study in June 2008 by Romero-Corral et al. examined xiii,601 subjects from the United states of america' third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES Three) and constitute that BMI-defined obesity (BMI ≥ 30) was present in 21% of men and 31% of women. Body fatty-defined obesity was found in 50% of men and 62% of women. While BMI-defined obesity showed high specificity (95% for men and 99% for women), BMI showed poor sensitivity (36% for men and 49% for women). In other words, the BMI will be mostly correct when determining a person to be obese, but can err quite often when determining a person non to be. Despite this undercounting of obesity by BMI, BMI values in the intermediate BMI range of 20–30 were found to exist associated with a broad range of body fat percentages. For men with a BMI of 25, about 20% take a torso fat percentage below 20% and well-nigh x% have body fat percentage above 30%.[42]

Body limerick for athletes is oftentimes better calculated using measures of body fat, equally determined by such techniques as skinfold measurements or underwater weighing and the limitations of manual measurement have also led to new, alternative methods to measure obesity, such as the body volume indicator.[ citation needed ]

Variation in definitions of categories [edit]

It is not articulate where on the BMI scale the threshold for overweight and obese should exist set. Considering of this, the standards accept varied over the by few decades. Betwixt 1980 and 2000 the U.S. Dietary Guidelines have divers overweight at a diversity of levels ranging from a BMI of 24.9 to 27.ane. In 1985 the National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus briefing recommended that overweight BMI be set at a BMI of 27.8 for men and 27.3 for women.

In 1998, an NIH study concluded that a BMI over 25 is overweight and a BMI over 30 is obese.[22] In the 1990s the Globe Health Organization (WHO) decided that a BMI of 25 to xxx should be considered overweight and a BMI over 30 is obese, the standards the NIH set. This became the definitive guide for determining if someone is overweight.

The electric current WHO and NIH ranges of normal weights are proved to be associated with decreased risks of some diseases such as diabetes blazon 2; however using the same range of BMI for men and women is considered arbitrary and makes the definition of underweight quite unsuitable for men.[58]

One study found that the vast bulk of people labelled 'overweight' and 'obese' co-ordinate to current definitions do not in fact face any meaningful increased run a risk for early on expiry. In a quantitative analysis of several studies, involving more 600,000 men and women, the everyman mortality rates were constitute for people with BMIs between 23 and 29; most of the 25–30 range considered 'overweight' was not associated with college run a risk.[59]

Alternatives [edit]

BMI prime [edit]

BMI Prime, a modification of the BMI arrangement, is the ratio of actual BMI to upper limit optimal BMI (currently defined at 25 kg/thoutwo), i.e., the actual BMI expressed every bit a proportion of upper limit optimal. The ratio of bodily body weight to body weight for upper limit optimal BMI (25 kg/m2) is equal to BMI Prime. BMI Prime is a dimensionless number independent of units. Individuals with BMI Prime less than 0.74 are underweight; those with between 0.74 and i.00 have optimal weight; and those at 1.00 or greater are overweight. BMI Prime is useful clinically because it shows by what ratio (e.yard. one.36) or percentage (e.m. 136%, or 36% above) a person deviates from the maximum optimal BMI.

For example, a person with BMI 34 kg/mtwo has a BMI Prime of 34/25 = 1.36, and is 36% over their upper mass limit. In South East Asian and Southward Chinese populations (see § international variations), BMI Prime should be calculated using an upper limit BMI of 23 in the denominator instead of 25. BMI Prime allows easy comparing between populations whose upper-limit optimal BMI values differ.[sixty]

Waist circumference [edit]

Waist circumference is a good indicator of visceral fatty, which poses more health risks than fat elsewhere. Co-ordinate to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), waist circumference in excess of 1,020 mm (40 in) for men and 880 mm (35 in) for (not-pregnant) women is considered to imply a high run a risk for type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and CVD. Waist circumference can be a better indicator of obesity-related illness risk than BMI. For case, this is the case in populations of Asian descent and older people.[61] 940 mm (37 in) for men and 800 mm (31 in) for women has been stated to pose "higher risk", with the NIH figures "even higher".[62]

Waist-to-hip circumference ratio has also been used, but has been establish to be no better than waist circumference lonely, and more complicated to measure.[63]

A related indicator is waist circumference divided by height. The values indicating increased run a risk are: greater than 0.five for people nether forty years of age, 0.5 to 0.vi for people aged 40–l, and greater than 0.6 for people over fifty years of historic period.[64]

Surface-based torso shape alphabetize [edit]

The Surface-based Torso Shape Alphabetize (SBSI) is far more rigorous and is based upon 4 fundamental measurements: the body surface area (BSA), vertical trunk circumference (VTC), waist circumference (WC) and summit (H). Data on 11,808 subjects from the National Health and Homo Diet Examination Surveys (NHANES) 1999–2004, showed that SBSI outperformed BMI, waist circumference, and A Body Shape Index (ABSI), an alternative to BMI.[65] [66]

A simplified, dimensionless form of SBSI, known as SBSI*, has also been adult.[66]

Modified body mass index [edit]

Within some medical contexts, such as familial amyloid polyneuropathy, serum albumin is factored in to produce a modified body mass alphabetize (mBMI). The mBMI tin be obtained by multiplying the BMI by serum albumin, in grams per litre. [67]

See besides [edit]

- Allometry

- Relative Fat Mass (RFM)

- Body water

- Corpulence index

- History of anthropometry

- List of countries by trunk mass alphabetize

- Obesity paradox

- Somatotype and constitutional psychology

Notes [edit]

- ^ e.g., the "Trunk Mass Index Table". National Institutes of Health's NHLBI. Archived from the original on 2010-03-10.

- ^ For instance, in the UK where people ofttimes know their weight in stone and height in feet and inches – see "Calculate your body mass index". xxx August 2006. Retrieved 2019-12-11 .

- ^ a b c d due east After rounding.

References [edit]

- ^ a b The SuRF Written report 2 (PDF). The Surveillance of Risk Factors Study Series (SuRF). World Health Organization. 2005. p. 22.

- ^ Di Angelantonio Eastward, Bhupathiraju Due south, Wormser D, Gao P, Kaptoge S, Berrington de Gonzalez A, et al. (August 2016). "Trunk-mass alphabetize and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents". Lancet. 388 (10046): 776–86. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(sixteen)30175-i. PMC4995441. PMID 27423262.

- ^ Eknoyan M (January 2008). "Adolphe Quetelet (1796–1874)--the boilerplate man and indices of obesity". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 23 (1): 47–51. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfm517. PMID 17890752.

- ^ Blackburn H, Jacobs D (June 2014). "Commentary: Origins and evolution of body mass index (BMI): continuing saga" (PDF). International Journal of Epidemiology. 43 (iii): 665–669. doi:ten.1093/ije/dyu061. PMID 24691955.

- ^ Vocaliser-Vine J (July 20, 2009). "Across BMI: Why doctors won't cease using an outdated measure for obesity". Slate. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ Keys A, Fidanza F, Karvonen MJ, Kimura N, Taylor HL (July 1972). "Indices of relative weight and obesity". Periodical of Chronic Diseases. 25 (half dozen): 329–343. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(72)90027-6. PMID 4650929.

- ^ a b "Assessing Your Weight and Wellness Take a chance". National Heart, Lung and Blood Found. Archived from the original on xix Dec 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ a b c "Defining obesity". NHS. Archived from the original on xviii Dec 2014. Retrieved nineteen Dec 2014.

- ^ "Physical status: the utilise and estimation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee" (PDF). Earth Wellness Organization Technical Report Series. 854: i–452. 1995. PMID 8594834. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-02-x.

- ^ "About Adult BMI | Salubrious Weight | CDC". world wide web.cdc.gov. 2017-08-29. Retrieved 2018-01-26 .

- ^ World Health Organization 2005, pp. 21–22.

- ^ "Body Mass Alphabetize: BMI for Children and Teens". Center for Disease Command. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-12-sixteen .

- ^ Wang Y (2012). "Chapter 2: Employ of Percentiles and Z-Scores in Anthropometry". Handbook of Anthropometry. New York: Springer. p. 29. ISBN978-i-4419-1787-4.

- ^ "Health Survey for England: The Health of Children and Young People". Archive2.official-documents.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2012-06-25. Retrieved 16 Dec 2013.

- ^ Ogunlade O, Adalumo OA, Asafa MA (2015). "Challenges of torso mass alphabetize classification: New criteria for young developed Nigerians". Niger J Health Sci. xv (fifteen:71–4): 71. doi:10.4103/1596-4078.182319. S2CID 132117809.

- ^ WHO Expert Consultation (January 2004). "Advisable torso-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies". Lancet. 363 (9403): 157–163. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. PMID 14726171. S2CID 15637224.

- ^ "Body weight chart – ideal goal weight nautical chart". Fitness of Body – Health & Wellness site.

- ^ "肥満って、 どんな状態?" [What is obesity, what kind of country?]. Obesity Homepage (in Japanese). Ministry building of Health, Labor and Welfare. Archived from the original on 2013-06-28. Retrieved 2013-05-25 .

- ^ Shiwaku K, Anuurad E, Enkhmaa B, Nogi A, Kitajima Chiliad, Shimono Thou, et al. (January 2004). "Overweight Japanese with body mass indexes of 23.0–24.nine have higher risks for obesity-associated disorders: a comparison of Japanese and Mongolians". International Periodical of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 28 (ane): 152–158. doi:x.1038/sj.ijo.0802486. PMID 14557832.

- ^ Kanazawa M, Yoshiike N, Osaka T, Numba Y, Zimmet P, Inoue Southward (December 2002). "Criteria and classification of obesity in Japan and Asia‐Oceania" (PDF). Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Diet. 11: S732-seven. doi:10.1046/j.1440-6047.11.s8.19.ten. : S734

- ^ "Trunk Mass Alphabetize (BMI)". Peter Yan Cardiology Clinic . Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Who's fatty? New definition adopted". CNN. June 17, 1998. Archived from the original on November 22, 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-26 .

- ^ World Health Organization (January 10, 2004). "Advisable torso-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies" (PDF). The Lancet. 363 (9403): 157–163. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15268-iii. PMID 14726171. S2CID 15637224. Archived from the original (PDF) on Dec 10, 2006.

- ^ Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL (June 2016). "Trends in Obesity Among Adults in the United states of america, 2005 to 2014". JAMA. 315 (21): 2284–2291. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.6458. PMID 27272580.

- ^ "Selected health conditions and risk factors, by age: the United states, selected years" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Anthropometric Reference Data for Children and Adults: United States" (PDF). CDC DHHS. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-02.

- ^ [[1] "Physical condition: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Commission"]. World Health Organization Technical Study Series. 854 (854): i–452. 1995. PMID 8594834. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-02-ten.

- ^ "Executive Summary". Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Prove Study. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. September 1998. xi–xxx. Archived from the original on 2013-01-03.

- ^ Bhaskaran One thousand, Douglas I, Forbes H, dos-Santos-Silva I, Leon DA, Smeeth Fifty (Baronial 2014). "Trunk-mass index and take a chance of 22 specific cancers: a population-based cohort study of five·24 one thousand thousand UK adults". Lancet. 384 (9945): 755–765. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60892-viii. PMC4151483. PMID 25129328.

- ^ Jaimes R, Rocco AG (2014). "Multiple epidural steroid injections and body mass index linked with occurrence of epidural lipomatosis: a case series". BMC Anesthesiology. fourteen: 70. doi:x.1186/1471-2253-14-70. PMC4145583. PMID 25183952.

- ^ Stokes A, Preston SH (December 2015). "Smoking and reverse causation create an obesity paradox in cardiovascular disease". Obesity. 23 (12): 2485–2490. doi:10.1002/oby.21239. PMC4701612. PMID 26421898.

- ^ Jeukendrup A, Gleeson Thou (2005). Sports Nutrition. Man Kinetics: An Introduction to Energy Production and Functioning. ISBN978-0-7360-3404-iii. [ page needed ]

- ^ Barasi ME (2004). Man Nutrition – a health perspective. ISBN978-0-340-81025-5. [ page needed ]

- ^ Dons E, Rojas-Rueda D, Anaya-Boig East, Avila-Palencia I, Brand C, Cole-Hunter T, et al. (October 2018). "Transport style selection and body mass index: Cross-exclusive and longitudinal evidence from a European-wide report". Environment International. 119 (119): 109–116. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2018.06.023. hdl:10044/1/61061. PMID 29957352. S2CID 49607716.

- ^ Stampler L. "France Simply Banned Ultra-Sparse Models". Time. Archived from the original on 2015-04-10.

- ^ ABC News. "Israeli Law Bans Skinny, BMI-Challenged Models". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2014-12-10.

- ^ Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH (April 2005). "Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity". JAMA. 293 (xv): 1861–1867. doi:ten.1001/jama.293.15.1861. PMID 15840860.

- ^ Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash Northward, Collins R, Peto R (March 2009). "Body-mass index and crusade-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies". Lancet. 373 (9669): 1083–1096. doi:x.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4. PMC2662372. PMID 19299006.

- ^ Walsh, Joe; Heazlewood, Ian Timothy; Climstein, Mike (July 2018). "Body Mass Index in Master Athletes: Review of the Literature". Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. viii (2): 79–98. doi:10.15280/jlm.2018.8.2.79. PMC6239137. PMID 30474004.

- ^ Lim JS, Lee DH, Park JY, Jin SH, Jacobs DR (June 2007). "A stiff interaction between serum gamma-glutamyltransferase and obesity on the risk of prevalent type 2 diabetes: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey". Clinical Chemistry. 53 (vi): 1092–1098. doi:x.1373/clinchem.2006.079814. PMID 17478563.

- ^ Romero-Corral A, Montori VM, Somers VK, Korinek J, Thomas RJ, Allison TG, Mookadam F, Lopez-Jimenez F (August 2006). "Clan of bodyweight with total bloodshed and with cardiovascular events in coronary avenue illness: a systematic review of cohort studies". Lancet. 368 (9536): 666–678. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69251-9. PMID 16920472. S2CID 23306195.

- ^ a b c

- ^ Schneider HJ, Friedrich Northward, Klotsche J, Pieper 50, Nauck M, John U, et al. (April 2010). "The predictive value of different measures of obesity for incident cardiovascular events and mortality". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 95 (4): 1777–1785. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-1584. PMID 20130075.

- ^ Mørkedal B, Romundstad PR, Vatten LJ (June 2011). "Informativeness of indices of blood pressure, obesity and serum lipids in relation to ischaemic middle disease mortality: the HUNT-2 study". European Journal of Epidemiology. 26 (half-dozen): 457–461. doi:10.1007/s10654-011-9572-7. PMC3115050. PMID 21461943.

- ^ "Aim for a Healthy Weight: Assess your Risk". National Institutes of Wellness. July 8, 2007. Archived from the original on 16 Dec 2013. Retrieved xv Dec 2013.

- ^ Kronmal RA (1993). "Spurious correlation and the fallacy of the ratio standard revisited". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 156 (three): 379–392. doi:10.2307/2983064. JSTOR 2983064.

- ^ Taylor RS (May 2010). "Letter to the editor". Paediatrics & Kid Wellness. 15 (5): 258. doi:ten.1093/pch/fifteen.v.258. PMC2912631. PMID 21532785.

- ^ Bonderud D. "What is the Ponderal Index?". The Health Board.

- ^ Sperrin (September 2016). "Body mass index relates weight to height differently in women and older adults: serial cantankerous-exclusive surveys in England (1992–2011)". Periodical of Public Wellness. 38 (3): 607–613. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdv067. PMC5072155. PMID 26036702.

- ^ Brody JE (31 August 2010). "Weight Index Doesn't Tell the Whole Truth". The New York Times. Archived from the original on ane May 2017.

- ^ Telegraph Reporters (21 January 2013). "Short people 'fatter than they remember' under new BMI". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 August 2015.

- ^ Diverse Populations Collaborative Grouping (September 2005). "Weight-summit relationships and trunk mass index: some observations from the Diverse Populations Collaboration". American Periodical of Physical Anthropology. 128 (one): 220–229. doi:ten.1002/ajpa.20107. PMID 15761809.

- ^ Levitt DG, Heymsfield SB, Pierson RN, Shapses SA, Kral JG (September 2007). "Physiological models of trunk composition and human being obesity". Diet & Metabolism. 4: 19. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-four-nineteen. PMC2082278. PMID 17883858.

- ^ "Why BMI is inaccurate and misleading". Medical News Today. 25 August 2013. Archived from the original on 2015-07-23.

- ^ "BMI: is the trunk mass index formula flawed?". Medical News Today. Archived from the original on 2015-07-23.

- ^ Lewis T (22 August 2013). "BMI Not a Good Measure of Healthy Trunk Weight, Researchers Fence". LiveScience.com. Archived from the original on 2015-07-21.

- ^ Trefethen North. "New BMI (Body Mass Index)". Ox.ac.uk. Mathematical Institute, University of Oxford. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Halls S (2019-02-18). "Platonic Weight and definition of Overweight". Moose and Doctor. Archived from the original on 2011-01-26.

- ^ Campos P, Saguy A, Ernsberger P, Oliver E, Gaesser 1000 (February 2006). "The epidemiology of overweight and obesity: public wellness crisis or moral panic?". International Journal of Epidemiology. 35 (ane): 55–60. doi:10.1093/ije/dyi254. PMID 16339599.

- ^ Gadzik J (February 2006). ""How much should I weigh?"--Quetelet's equation, upper weight limits, and BMI prime". Connecticut Medicine. 70 (2): 81–88. PMID 16768059.

- ^ "Obesity Teaching Initiative Electronic Textbook - Treatment Guidelines". United states of america National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on i May 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ "Why is my waist size important?". U.k. HNS Choices. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ "Waist Size Matters". Harvard School of Public Health. 2012-10-21. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ HospiMedica International staff writers (18 Jun 2013). "Waist-Height Ratio Better Than BMI for Gauging Mortality". Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ Pomeroy R (29 Dec 2015). "A New Potential Replacement for Body Mass Index | RealClearScience". www.realclearscience.com. Archived from the original on 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2015-12-31 .

- ^ a b Rahman SA, Adjeroh D (2015). "Surface-Based Body Shape Index and Its Relationship with All-Cause Mortality". PLOS Ane. 10 (12): e0144639. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1044639R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144639. PMC4692532. PMID 26709925.

- ^ Tsuchiya A, Yazaki Thou, Kametani F, Takei Y, Ikeda S (April 2008). "Marked regression of abdominal fatty amyloid in patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy during long-term follow-upwardly after liver transplantation". Liver Transplantation. 14 (4): 563–570. doi:10.1002/lt.21395. PMID 18383093. S2CID 13072583.

Further reading [edit]

- Ferrera LA, ed. (2006). Focus on Body Mass Index And Health Research. New York: Nova Scientific discipline. ISBN978-1-59454-963-2.

- Samaras TT, ed. (2007). Human Body Size and the Laws of Scaling: Physiological, Performance, Growth, Longevity and Ecological Ramifications. New York: Nova Science. ISBN978-ane-60021-408-0.

- Sothern MS, Gordon ST, von Almen TK, eds. (xix April 2016). Handbook of Pediatric Obesity: Clinical Management (Illustrated ed.). CRC Printing. ISBN978-1-4200-1911-7.

External links [edit]

- U.Southward. National Center for Health Statistics:

- "BMI Growth Charts for children and young adults". Us Centers for Affliction Control and Prevention. 31 January 2019.

- "BMI estimator ages xx and older". U.s. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 21 July 2021.

lunsfordconand1977.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Body_mass_index

0 Response to "Baby Boy Weight Chart in Kg 1 Year and 7 Month Old"

Publicar un comentario